Administrators and teachers love the beginning of a new school year. The anticipation of a new group of students in a teacher’s class, meeting new families and greeting familiar friends, opportunity for new learning; in general, the beginning of the year can bring great joy and sometimes great dread.

All too often the past school year ended with plans and a vision to take into the new year. Sadly, in many cases that is not the reality to which administrators and teachers return. Over the summer members of the district office have received new mandates from the state or federal levels that end up impacting the plans schools have made. Sometimes, it’s a whole new path for professional learning, one that was not anticipated by schools at the end of the previous year. This situation can be at the least frustrating and at the most can erode trust between the district office leaders and the teachers and staffs at the school level.

And so, it’s not unusual for the question “And what does the District want now?” to be raised.

So how can some continuity be brought to a situation over which there may be little control? In districts where Targeted Leadership Consulting works there is a process to address this challenge. In the Chula Vista Elementary School District, a representative group called the Design Team exists. Membership includes District Office leaders, school level administrators, teacher union representation, site level teachers, and outside experts that support learning development. Their charge is to examine data and develop a district instructional focus that is be tight enough to unite the work of the Educational and Support Services department and the schools; and loose enough to allow schools flexibility in choosing how to address the expectation of the District Instructional Focus.

The District Instructional Focus is the guide for aligning all training and professional learning offered at the school level and district level by either internal presenters or external presenters.

In Chula Vista, the Design Team came together after Year 2 to reflect on the work accomplished and to develop the goal for Year 2. Input was given as to what the content for the Instructional Leadership Team sessions should include. Teacher input was critical for developing these goals.

At the end of the year, the plans and session topics were presented to teachers and administrators. The Instructional Focus is the same. The Instructional Leadership Team (ILT) learning for this year builds on the learning from last year. Many commented there is clear evidence of the input from the group.

Administrators and teachers love a new beginning. The anticipation of a new group of students in a teacher’s class, meeting new families and greeting familiar friends, opportunity for new learning; in general, the beginning of the year can bring great joy and this year the answer to the question of “What does the district want now?” is one that has a clear answer!

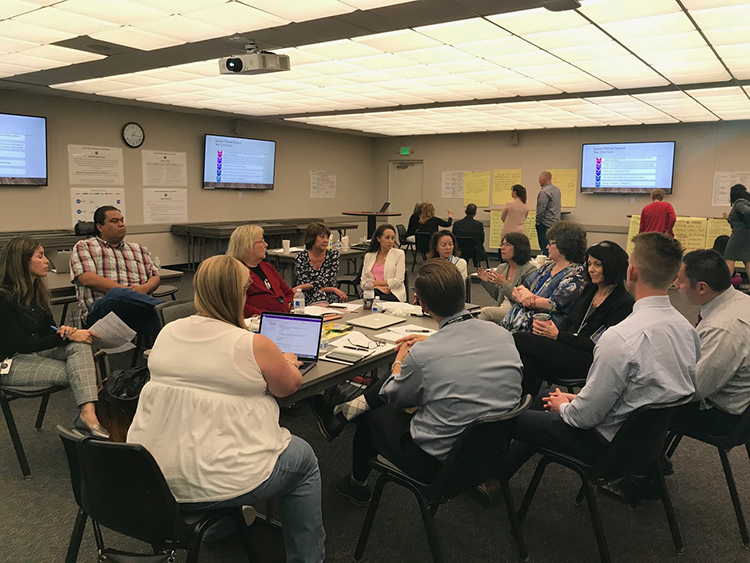

Teacher and district leaders working collaboratively to establish the content for each session of the Instructional Leadership Team work.

Teacher and district leaders creating goals for the Instructional Leadership Team work of Year 2.

How do we get better as teachers? How do we improve our teaching practice? As leaders, how do we establish learning for our teachers so they can deepen their understanding of pedagogy? How can we share best practices across the entire school system?

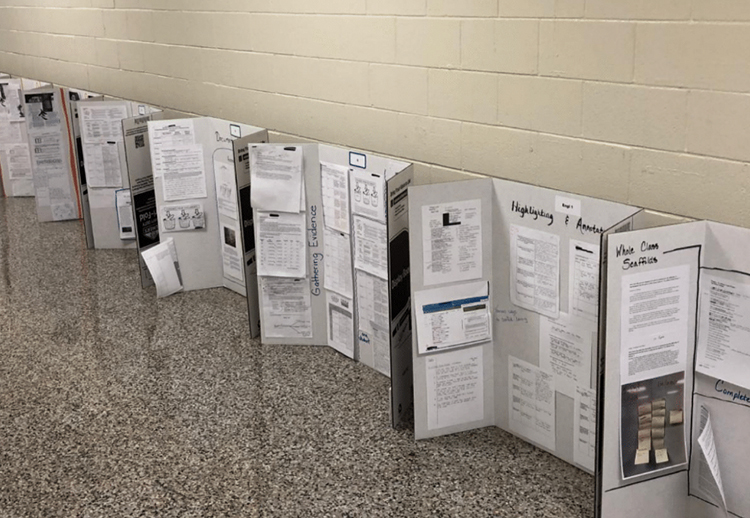

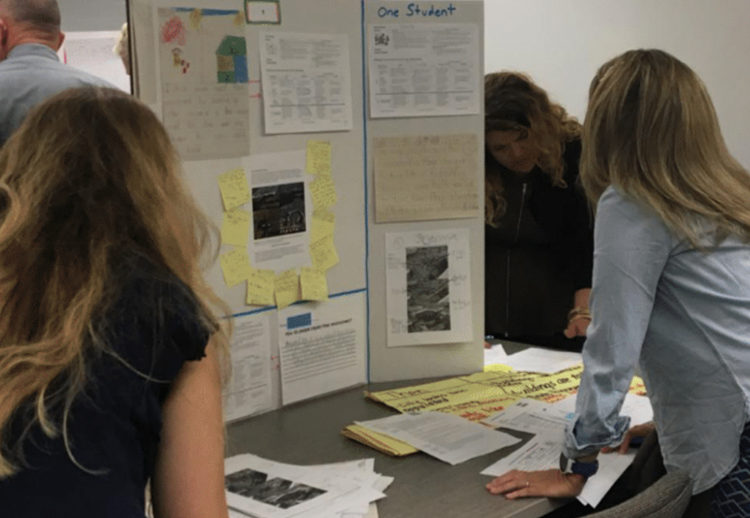

One district did just that by organizing a district-wide “Looking at Student Work” protocol. Recently, in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, teachers administered a district-wide Cornerstone Lesson Project that consisted of vertically aligned lessons. Each cornerstone lesson focused on either science and social studies standards as well as close reading and writing with evidence. Pre-Kindergarten through high school, students and teachers completed these lessons in over 150 schools. School teams were invited to submit samples of student work connected to the Cornerstone Lesson Project.

During their recent Instructional Leadership Teams Networking Celebration , over 900 of CMS teachers leaders, principals and district staff engaged in what the CAO called the “Vertical Slice that should go down in the Guinness Book of World Records!” Through a structured and safe protocol, teachers examined the tasks, student work samples, and rubrics to determine how well students met the demands of the task and mastered the content standards to which the tasks were aligned. They also compared the work spanned by all grade levels. This powerful professional learning experience gave teacher leaders and administrators the opportunity to examine standards aligned tasks from grades PreK to 12.

Three key tips for making a large-scale vertical slice happen in your school or district center on processes for improvement.

Focus on practices, not people.

The groundwork for this celebration was three years in the making. Trust and a mindset of improvement is built over time. “Teachers must be willing to expose their struggles and failures with their colleagues,” Elisa MacDonald writes. And “colleagues must be willing to tell the truth, or teams will go through the motions … but never see results” (p. 45). Use a protocol to keep the emphasis on the student work and the instructional practices.

Focus on student thinking

The vertical slice emphasizes skills and practices beyond the rudimentary instead asking for analysis of instructional practices associated with district-wide professional learning around literacy. Do you see evidence of student interaction with complex text? Are students writing based on that text? What evidence of their thinking is obvious? What patterns do you see across schools? Across grade levels? By focusing on student thinking, we get to the heart of the discussion. Are all students provided the same access to quality instructional practices and the same level of expectations to high standards?

Focus on improvement of practice.

Finally, this process provides an in-road to teacher reflection. Teachers can collaboratively share while still holding an internal dialogue to improve personal instructional practices. How does the work of my students look compared to this continuum of work displayed? Where do my students fit? Do I need to up my game?

Opening up instructional practice by sharing student work requires a great deal of vulnerability and trust. When teachers co-plan lessons and tasks and analyze the student work associated with the tasks, they are able to calibrate on how well students the mastered content standards.

There is power in opening our practice – for districts, for schools, and for teachers. When we share our work, teaching and learning improves.

——

MacDonald, E. (2011). When nice won’t suffice: Honest discourse is key to shifting school culture. Journal of Staff Development, 32(3), 45–51.

We often hear that teachers dread attending district level professional development.

One complaint often used is that the training offered by districts “has little or no application to real work in the classroom.”

Nothing can be further from the truth in the Ferguson/Florissant School District in Missouri where teacher leaders in each school’s instructional leadership team, join together 6 times a year for a full day of learning best practices and sharing how these practices are impacting student learning.

These collective learning PD days prepare teacher leaders to go back to their colleagues and lead training at their schools.

What are the results for teachers? Increased implementation of powerful practices such as “Close Reading” across all grade levels and content areas.

What are the results for students? Increased number of students using “Close Reading” to read and understand texts that are more complex.

Can you say the same about the work in your district?

Share your successes in the comments section below:

Welcome to TLC Talk.

Our goal is to support principals and schools who are distributing and developing leadership to improve student learning at their schools – primarily through the use of an Instructional Leadership Team (ILT). We will be sharing the work we’re doing and the lessons we’re learning with schools and districts across the country like Charlotte, Chicago, Baltimore, Chula Vista, Fontana, Oahu, Orlando, Ferguson, and others. We encourage readers to respond with question as well as with perspectives and examples gleaned from your own experiences.

Jeff Nelsen and Amalia Cudeiro

Today we want to share an article that describes what we have found to be a key responsibility for Instructional Leadership Teams – promoting and managing the Professional Learning across the school.

The literacy coach approaches the principal, beaming and clearly energized. “That was one of the best professional development sessions we’ve had here! It was clear, creative, provided useful and practical information, engaged the teachers in dialogue and modeling, and even provided them with all the materials they’ll need to implement the practices that were presented. I think having everyone use these strategies on a regular basis will really take care of our reading comprehension problem.” The principal is also smiling and agrees that it was an excellent session. The principal congratulates the coach on her good work and agrees that the staff left feeling empowered. As the principal reflects on the day, however, he is very aware that the research shows that even successful, high-quality professional development leads to about a 5% implementation rate. The principal makes a note in his planner to schedule a session with the coach the following morning to discuss plans for additional strategies necessary to ensure that teachers continue to learn and implement what they learned today.

MAKING A CULTURE SHIFT

How can schools shift from isolated incidents of professional development to a culture of professional learning? Most professional development plans and strategies simply offer high-quality training or activities that teachers then decide how (or if at all) to implement in their classrooms (Fullan, 2007). By using a targeted professional learning plan, schools can increase the likelihood of student success by using cycles of learning to incorporate professional development lessons into daily school and classroom rhythms.

The professional learning model detailed here is designed around repeated cycles of learning sessions lasting six to eight weeks linked with supports such as observation and coaching, professional readings, looking at student work, peer observations, and walk-throughs. Such supports are essential for full implementation of the learning in every classroom for every student every day (Joyce & Showers, 2002). Taken together, these actions have the potential to move a school a giant step forward toward coherence and tighter coupling, where what and how students are learning is a matter of common knowledge (Elmore, 2000), and most importantly, leading to a culture where adult learning becomes as common as student learning.

TARGET A FEW INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES

As is often the case, less is more when it comes to establishing a culture of professional learning. If we’re trying to build true expertise in each faculty member rather than just expose them to the ideas, we cannot really expect to implement all of Marzano’s strategies or all six components of balanced literacy in the same year. Since a school can reasonably expect to build true expertise in only one or two instructional practices per year, it is important that educators select powerful strategies. A good illustration of this comes from 110 high schools in Chicago that have recently begun implementing a new model of professional learning, and with help from the district’s academic coaches, have identified powerful practices that teachers model in their instruction in such a way that they become learning practices that students can use throughout their schooling.

THE MODEL: CYCLES OF PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

The intent of this model is to create a professional learning plan that builds expertise in all staff through repeated cycles of high-quality learning, followed by opportunities for practicing, receiving feedback, observing colleagues, ongoing professional reading, and peer discussion about the practices, including examining the impact of the practices on student learning by looking at student work and reviewing student performance data. Key concepts of the model are:

Repeated cycles

In order for teachers to master instructional practices and add them to their repertoire, it is necessary for them to be engaged in all aspects of professional learning at least four times before they can be expected to have full mastery of that strategy (Saphier & Gower, 1997). Many schools plan on a cycle per quarter since each cycle takes six to eight weeks of learning sessions. A typical scenario might look as follows:

Weeks 1-2: Teachers participate in professional learning about a targeted instructional area, such as reading comprehension, and teachers begin to practice what they have learned in their classrooms. Professional reading begins on a weekly basis.

Weeks 3-6: Teachers schedule time to observe each other using the newly learned strategies. The instructional leadership team, administrative team, and others begin visiting classrooms on targeted learning walks to see what additional training or support teachers need. Instructional coaches schedule time to observe teachers and give feedback. Teacher collaboration teams meet regularly to discuss implementation of the new practices and the impact of the practices on student learning by looking at student work and course assessment data.

Weeks 7-8: All activities described above continue. The instructional leadership team visits all classrooms to measure the level of implementation of the powerful practices across the school and modifies their plan for the next cycle based on the data received.

Quality learning opportunities

While some schools and districts have the internal capacity to provide direct training to their teachers, others seek out experienced training partners to guide them through this process. Introducing new concepts and skills to teachers through high-quality learning led by seasoned professionals with knowledge of the practices is critical if we expect teachers to implement a strategy or practice in a classroom setting. Quality learning includes explanation of the concepts underlying the practice, modeling how the practice would look in a classroom, connecting the practice to research and results, providing strategies for differentiating for learners at different levels, giving participants opportunities during the training for experimentation and discussion, and introducing all materials needed to implement the practice.

Opportunities for safe practice

Allowing teachers multiple chances over several weeks to experiment with the new strategies in a low-risk environment, such as their own regular teaching settings, is another important consideration. While part of the intent of this model is to open up practice and get more people into more classrooms more often, the first week or two after a learning session is not a good time for administrators who evaluate teachers to go into classrooms with a checklist. Teachers need time to gain confidence with the new skills, and confidence grows best in supportive cultures.

Observing colleagues

Many teachers learn best by observing colleagues using the strategy they are attempting to learn themselves. Having each teacher observe several other teachers practicing the new strategy and discussing what they observed in the initial learning sessions can be a powerful support. It also gives teachers the opportunity to develop a common vocabulary around the new practice and sends a strong message that “we’re all in this together.”

Receiving feedback

Learning occurs at a deep level when a teacher is thinking about good practice while implementing the strategy. Observation by a coach or peer teacher, paired with structured feedback that reinforces teachers’ positive actions and suggests specific improvements, is an effective, research-based tool for building mastery.

Professional reading

The knowledge base about effective teaching practice is growing constantly, yet few teachers have the time to identify it. We have seen a powerful impact when schools make it easier for teachers to stay informed about new findings by having a specific plan for providing highlighted articles weekly to teachers tied directly to the focus of the current professional learning cycle. The expectation is that each person will quickly review at least the highlighted sections of each article and that occasionally they will discuss articles with peers. Using this strategy, in one school year, teachers will review at least 36 articles that support and clarify the work they are doing.

Peer discussion/looking at student work/data review

Many scholars posit that learning is essentially a social activity, and that people make meaning through conversation. Having teachers meet in teams on a regular basis to discuss the successes and challenges of implementation is a critical part of professional learning.

Opportunities for looking at student work and reviewing student assessment data to monitor the impact of new instructional strategies on student learning help teachers see why they need to make changes in their practice. This process gives teachers the data that will inform how they adjust their use of the strategies according to specific student needs.

Monitor, measure, and modify

The ongoing process of having the principal, the instructional leadership team, and other school leaders conduct frequent visits to all classrooms to have a clear understanding of the implementation level of new practices begins in the third week of the cycle. This is NOT part of the teacher evaluation process, but is rather a means to gather informal data and to facilitate good decisions about future learning and resource allocation (Cudeiro, 2009).

Measuring the implementation level across the school during the final week of the cycle allows the leadership to modify plans for the next cycle, so that the consistent level of expertise across the staff builds from cycle to cycle.

VISION BECOMES REALITY

Imagine a classroom where students of different ages are working together in small groups on projects selected by their area of interest. The teacher circulates with a clipboard, helping as needed and making notes about student mastery level of different standards.

Another educator enters the room, observes for a while, then makes specific suggestions to the teacher about how to increase the rigor of the work for some small groups. The visitor leaves the room, and the teacher turns to the student groups with modifications for their work.

Or imagine being invited to a school’s faculty meeting, where a teacher describes her visit to a colleague’s room earlier in the day, when she observed that several students

were not paying attention. The teacher who was observed agrees that the new strategy she was trying after their recent professional development did not go as well as she had hoped and asks the group for suggestions. Another teacher describes using the strategy to great effect in her room and invites the teacher to come and observe the following morning. After the group arranges to cover the visiting teacher’s class, they move on to another challenge.

Sound too good to be true? These schools are among many examples of previously underperforming schools that are now exemplary models of learning. That’s not an accident. While creating a professional learning community at any school is challenging, it can only happen through intentional leadership.

Being strategic about what teachers need to learn and implementing a targeted professional learning plan with repeated cycles that provides teachers with the support they need to develop expertise are great ways to move toward that goal as well as toward the ultimate goal of improving student learning.

REFERENCES

Cudeiro, A. (2009, January/ February). The next generation of walkthroughs. Leadership, 38(3), 18-21.

Elmore, R. (2000). Building a new structure for school leadership. Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute.

Fullan, M. (2007). The new meaning of educational change. New York: Teachers College Press.

Joyce, B.R. & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Saphier, J.D. & Gower, R. (1997). The skillful teacher: Building your teaching skills. Acton, MA: Research for Better Teaching.

Click here or on the image below to view the article

QUESTIONS