We include below links to various articles dealing with improving student achievement and leading system-wide reform. These articles are written by Targeted Leadership senior executives and consultants.

>> Printable On Target Version | Published in The School Administrator April 2009

In his national best seller, The Tipping Point, Malkcom Gladwell introduces the concept of organizational change as an epidemic. He suggests that ideas, products, messages and behaviors spread just like viruses. That dramatic moment when powerful change happens seemingly all at once is usually characterized by a person-to-person spread of ideas and practices and the realization that little changes have big effects. Once changes or innovations reach the “Tipping Point” they spread throughout the organization and become entrenched as part of the culture and become “just the way we do things around here.” This article uses the Tipping Point frame in connection with systemic improvement in two urban school districts, examining how lessons learned in those settings may help other districts accomplish similar success.

Springfield, Illinois and Chula Vista, California have spent the past five years collaborating in a three-way partnership with the Ball Foundation, who provided financial support and direct coaching, and a group of external consultants who provided training in leadership capacity development directly connected to improving classroom instruction. In each of these districts, the initial emphasis of the work was with a small number of schools and the central office leaders that served those schools. Only a small number of schools were added to the program each year, yet after only three years, each district had reached the “Tipping Point” and the growth and improvements implemented in the small number of schools involved had spread throughout the districts. In Lowell Billings words, “it became clear that success was not predicated on what school staff did, but rather on what they did together.”

What follows is a description of Lessons Learned about the successful process of addressing whole district systemic improvement without involving the whole district in intensive and costly training and support.

When an organization reaches the Tipping Point it signifies a change in culture within the organization. What was formerly a new idea, approach or practice is now just “the way we do things around here.” The fact that so many good ideas never become common practice testifies to the great difficulty in accomplishing this type of culture shift. We have found that the way a new initiative is begun has a powerful impact on whether or not it lasts. Here are a few things to consider as you plan the work in your district.

Allow schools a choice in participating

In each district, there was a presentation of the work of the partnerships very early in the process, with a clear set of expectations given to guide the selection and involvement process. A small group of five schools and the central office leaders were chosen to participate in the training and coaching to be provided for this phase of the program. The intent was clear from the beginning – this was not to be an isolated program, but rather something that was intended to eventually impact the whole district. In Chula Vista, the first cohort of five schools to participate was allowed to self-select, after a small amount of encouragement by the superintendent and the foundation leaders. Springfield joined the process a year later, after studying the gains made by the first group in Chula Vista. Here the Superintendent personally invited the schools to participate, a few low-performing schools were strongly encouraged to join the cohort, while the others self-selected and felt honored to be chosen. One key point is that throughout the process none of the cohorts were made up of all low-performing schools or of schools that were ordered to participate.

Provide direct training and coaching in collaborative instructional leadership

In “Learning Together,” Michael Fullan states that “student learning depends on teachers learning all the time. We must make professional learning an everyday experience for all educators.” This is not the culture of most schools, however, and to shift the existing structures and practices toward this new culture requires explicit direction and support. Each cohort of schools and the central office team received three years of structured training and coaching designed to build instructional leadership capacity with a team of five to ten teachers and the principal at the school, called the Instructional Leadership Team. The training included five to eight full day sessions per year with on-site coaching and walkthrough visits between each training session. The training centered around concepts for understanding and tools for implementing this researched-based, experience-proven Framework:

Central office teams received direct training and coaching to help shape their roles to be more clearly in support of the instructional leadership of the principal and ILTs at the schools in implementing the framework. Bob Hill, the Director of the Ball Foundation has stated that the training “de-isolated teachers and teaching. The introduction of rigor into the practice of ILTs, having principals and teachers experience professional learning together, and finding creative solutions to finding time for collaboration and grade level teams all were examples of early progress. Coaching of principals, teachers and district level staff is viewed as critical to the success of the partnership.”

Communicate openly with all affected

Additional stakeholder groups, such as teacher union leaders, school boards, and parent leadership groups were kept appraised of the training and its implications for practice. In both districts the union president participated in the training, and having the teacher union leadership directly involved in training sessions as a partner with the superintendent led to increased communication and support for the initiative. In Springfield there were direct training sessions offered to both parents and the school board.

Celebrate Short-Term Wins

In his book Change, John Kotter lists a failure to celebrate short-term wins as one of the eight errors continually made by organizations in transformation. In our work in these districts, we ask schools to think about what these short tem wins might be and then help them craft the communication plan to celebrate their success. Reinforcing success is one of the best ways to reward teachers and leaders for their work and to engage reluctant participants. It also has a powerful impact on other schools that are watching; each district had more volunteers for the second Cohort than they were able to accommodate, because they had heard so much about the success of the first group.

Some short-term wins that have generated increased enthusiasm for the work have been as simple as:

When entry is done well it can actually create difficulty for the expansion phase. There is often a tendency to think that the first group is now well on its way and the focus can shift to a new group; there is also a tendency to make the new group too large in order to include everyone interested in participating. Here are some things to consider when you begin to expand the work in your district.

Gradually roll out the work

After an initial cohort of schools has been established in year one, the plan for expansion needs to be purposeful and deliberate. When possible, the concept of this being “by invitation” or self-selected participation, leads to better buy-in and ultimately stronger implementation. Leadership must be mindful that each cohort should have a limit on the number of schools participating in each cohort. Controlling the number of schools ensures a gradual rolling out of the work. Lowell Billings, the Superintendent in Chula Vista, stresses that “the key is to emphasize that adherence to the framework is a school by school process – there is never a rote procedure.”

Embed the work in the culture

As each new cohort receives training, the presence of members of Central Services becomes more prominent. Upfront training is now shared by the outside consultant and in-house leadership. The involvement of Central Services at this level sends the message that this work is shared by schools and central services. As Central Services supports the work of all schools in the district the practices, vocabulary and expectations become more systemic.

Maintain the work started with the initial cohort

After the first year, the work with the initial cohort and each succeeding cohort is maintained through continued Institutes, visits to schools and coaching. In addition, the leadership role they play increases. Cohort 1 is brought in to share their experiences and stories with Cohort 2, Cohort 2 has the same opportunity with later cohorts. The work of Central Services across the district becomes more aligned to the Framework and so the work with subsequent cohorts moves at a faster pace because practices and vocabulary initially introduced with Cohort 1 are now more systemic.

Consistency across the district

As each cohort is introduced to the Framework, and Central Services begins to align their work to the needs of schools, there is a consistency that begins to exist across the system. Although the work of each cohort moves at a faster pace because of the standard set by each preceding cohort, the Framework, vocabulary, practices and procedures are consistent and yet flexible enough to support the individual needs of each school and district level work.

Slow is Better

As tempting as it can be to take the work to a wider scale quickly once schools in the initial cohort have seen success, a lesson learned is to take the time to be deliberate in how the initiative is implemented across the district. Taking time to reflect on what worked with each cohort and customize the trainings to each new group of schools will serve the schools and system better. As mentioned earlier, the pace of the implementation moves faster with each additional cohort because the Central Services is aligning their work to the Framework.

Sustaining Phase

From the beginning of this partnership, everyone agreed that the improvements should last longer than the partnership. The goal was that through training and coaching, the leadership of the schools and the district would develop the capacity to sustain the work of continuous improvement long after the consultants had gone. This has become the case in both districts, and it hasn’t happened accidentally. Careful planning from the beginning is necessary to assure that capacity and ownership transfers to district leaders. Here are some of the conscious efforts that were put in place to assure sustaining the work.

Set clear expectations for implementation

The question of building capacity within a district is one of the key issues facing districts as they seriously consider district-wide expansion of their reform. The issue really is how to tie the school reform ideas learned in institute sessions and discussed by instructional leadership teams into the everyday life of schools in a manner that it becomes a natural part of their daily life and not regarded as “the add on” or yet one more “new idea”.

We have found in both Chula Vista and Springfield school districts that the institute work has to be very deliberatively woven into everyday school life and that the most successful way to do this work was to ask each ILT to develop next steps for their work over a period of 4-6 weeks in their schools. The subsequent institute would start with a session called connections where schools reflected and reported their successes and lessons learned. This provided them with material to share with other schools, held them accountable, and provided that vital thread that tied one institute to the next through the school life on a daily basis. Many schools started using this same strategy to link the work and raise accountability as a format for many of their grade level team meetings. Presenters at the institute were also deliberate about suggestions regarding possible next steps schools should consider. They were also very clear about the questions coaches would ask when in schools.

Move from Central Office to Central Services Many schools labeled this part of the work the “no surprise session” – no surprises for anyone about what we were being held accountable for. The involvement of central services in this capacity building is critical; central staff must be seen as collaborators.

It is really a three-part process for central services:

In Springfield, the district now operates the Focus Implementation Team (FIT) for the purpose of sustaining the knowledge introduced to the system by the technical assistance partner. Members of that team have received training provided for the specific purpose of supporting sustainability.

The Instructional Support Services (ISS) team serves the same function in Chula Vista. Diane Rutledge, former Superintendent of Springfield Public Schools, adds that “this effort requires a systems approach. We created a continuum from the classroom to the boardroom with everyone pulling in the same direction.”

Watch Closely for Signs of Tipping

Each school district is a unique organization, and each has a story to tell about tipping points – about the one “event” that suddenly made it crystal clear that there was no turning back, that the whole district was now on board. In Springfield, one of these key moments occurred when all the high schools voted and asked to become part of the training along with some middle and elementary schools. The district sat up and took notice – “if the high schools are all in, we might as well all be in,” so this seemingly small event had a huge impact. In Chula Vista, it was when Superintendent Lowell Billings began the annual administrator retreat by “strongly encouraging” every school to implement the Cohort Expectations for the year whether they were involved in the training or not. He used increases in student performance at the Cohort schools to support his statement. Each sign of the culture shifting throughout the process is a cause for internal celebration and provides key support and direction for moving the work forward.

One of the subtle, yet powerful, indicators of “tipping” that occurred in both districts prior to the defining events noted above was the migration to a common vocabulary about school improvement that permeated both systems prior to some schools’ becoming members of a learning cohort. Bob Hill recalls conversations with the superintendents in both districts in which they observed how “adoption of a common vocabulary about school improvement is a powerful indicator of the tip toward a changing culture.” It may be important to note as one indicator of having reached the tipping point that both Springfield and Chula Vista have changed Superintendents since the work began. Despite changes in top leadership, the work continues to expand and to yield measurable improvement in both districts to this day.

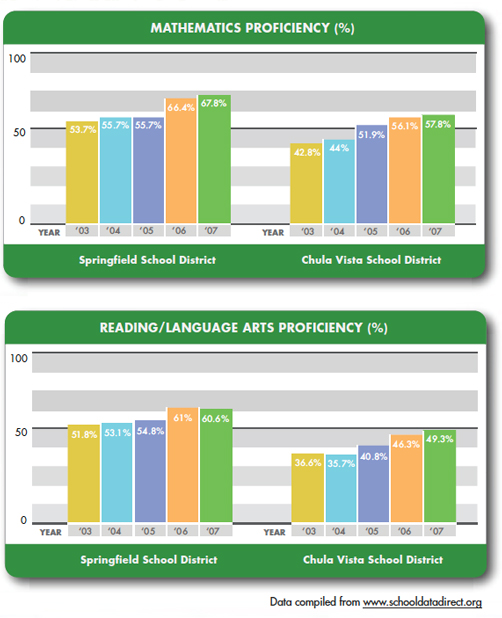

Both districts have seen dramatic improvement in student learning across their schools. To accomplish this in a single school is very challenging. To accomplish this in a cohort of schools is formidable. Yet both Springfield and Chula Vista are districts that have made huge progress toward this culture shift throughout their entire systems as a result of sustained collaboration with a supportive operating foundation and a strong technical assistance provider. Reaching the Tipping Point and moving an entire district in the direction of continuous improvement in teaching and learning is worth the time and effort required to build and sustain such partnerships.

Below are data graphs that show the district wide growth in student achievement for both Springfield and Chula Vista as a result of the three way collaboration effort between the Ball Foundation, Springfield and Chula Vista Central Services teams, and the consulting firm providing the services.

Jeff Nelsen, Ph.D. is a Partner in Targeted Leadership Consulting and has worked in both Springfield and Chula Vista providing some of the training and coaching described above.

Bob Hill is the Director of Education Initiatives at the Ball Foundation and continues to work in both Springfield and Chula Vista in the foundation’s partnership sustainability efforts.

Diane Rutledge, Ph. D. is the former Superintendent of Springfield Public Schools and currently the Executive Director of Large Unit District Association for the state of Illinois.

Lowell Billings is the current Superintendent of Chula Vista Elementary School District.

>> Printable On Target Version | Published in The School Administrator April 2009