How do we get better as teachers? How do we improve our teaching practice? As leaders, how do we establish learning for our teachers so they can deepen their understanding of pedagogy? How can we share best practices across the entire school system?

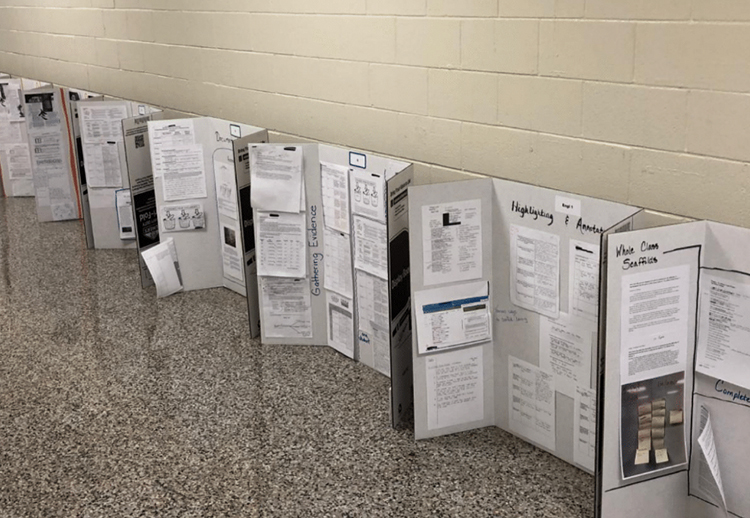

One district did just that by organizing a district-wide “Looking at Student Work” protocol. Recently, in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, teachers administered a district-wide Cornerstone Lesson Project that consisted of vertically aligned lessons. Each cornerstone lesson focused on either science and social studies standards as well as close reading and writing with evidence. Pre-Kindergarten through high school, students and teachers completed these lessons in over 150 schools. School teams were invited to submit samples of student work connected to the Cornerstone Lesson Project.

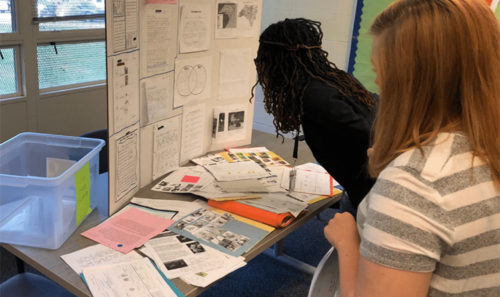

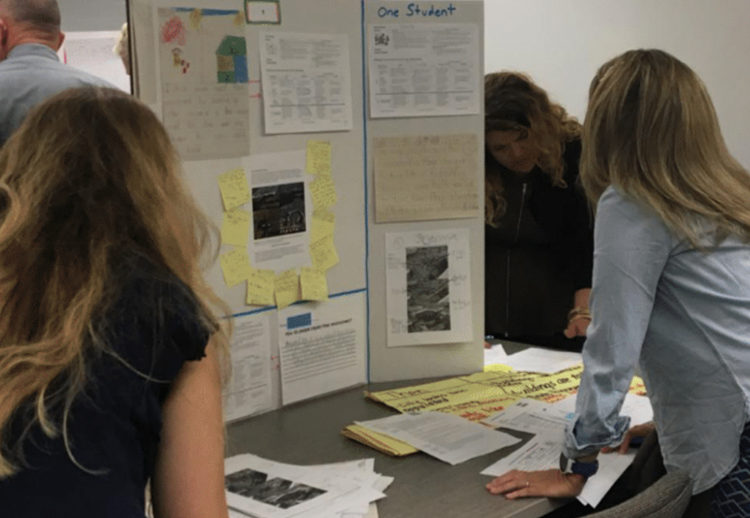

During their recent Instructional Leadership Teams Networking Celebration , over 900 of CMS teachers leaders, principals and district staff engaged in what the CAO called the “Vertical Slice that should go down in the Guinness Book of World Records!” Through a structured and safe protocol, teachers examined the tasks, student work samples, and rubrics to determine how well students met the demands of the task and mastered the content standards to which the tasks were aligned. They also compared the work spanned by all grade levels. This powerful professional learning experience gave teacher leaders and administrators the opportunity to examine standards aligned tasks from grades PreK to 12.

Three key tips for making a large-scale vertical slice happen in your school or district center on processes for improvement.

Focus on practices, not people.

The groundwork for this celebration was three years in the making. Trust and a mindset of improvement is built over time. “Teachers must be willing to expose their struggles and failures with their colleagues,” Elisa MacDonald writes. And “colleagues must be willing to tell the truth, or teams will go through the motions … but never see results” (p. 45). Use a protocol to keep the emphasis on the student work and the instructional practices.

Focus on student thinking

The vertical slice emphasizes skills and practices beyond the rudimentary instead asking for analysis of instructional practices associated with district-wide professional learning around literacy. Do you see evidence of student interaction with complex text? Are students writing based on that text? What evidence of their thinking is obvious? What patterns do you see across schools? Across grade levels? By focusing on student thinking, we get to the heart of the discussion. Are all students provided the same access to quality instructional practices and the same level of expectations to high standards?

Focus on improvement of practice.

Finally, this process provides an in-road to teacher reflection. Teachers can collaboratively share while still holding an internal dialogue to improve personal instructional practices. How does the work of my students look compared to this continuum of work displayed? Where do my students fit? Do I need to up my game?

Opening up instructional practice by sharing student work requires a great deal of vulnerability and trust. When teachers co-plan lessons and tasks and analyze the student work associated with the tasks, they are able to calibrate on how well students the mastered content standards.

There is power in opening our practice – for districts, for schools, and for teachers. When we share our work, teaching and learning improves.

——

MacDonald, E. (2011). When nice won’t suffice: Honest discourse is key to shifting school culture. Journal of Staff Development, 32(3), 45–51.

Exciting to see a concentrated effort system-wide. My most sincere congratulations to the teachers in Charlotte.

So exciting to see teachers sharing their work in a non threatening way. Excellent way to learn from each other

Premises are not diffeent from industrial model of assembly line with teachers at every grade working on “tasks

aligned with “standards” set by others, and with “mastery” of little chunks of knowledge (called tasks) expected, on time, in each grade, presumably with no loss of learning grade to grade. The required comparisons across classrooms, grade levels, and schools help to divorce the concept of “improvement” from the myriod differences between actual classrooms and job assignments of teachers. Text complexity is a deeply flawed concept and the idea that literacy is independent of content and life experience is absurd. Teachers need to be critical of the premises and ends-in-view of dog and pony shows originating from afar and in this case with substantial funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

What’s so impressive is that a school system of this size, with more than 9,000 teachers, managed to collaborate and learn from one another in such a meaningful way. This truly speaks to the strong leadership model that must be in place, with student learning at the center of it all!